Welcome to part I of a three-part post about the history of zoning in Los Angeles. Zoning and land-use regulation represent the outcome of battles pitting one political group against another: open land speculators versus large tract developers versus no growth homeowners versus pro growth renters. Some groups dominate their specific time or regime while other groups work together to pull control away from the dominant group.

It should be said that much of the information I’m presenting is based on a July 2012 article by Dr. Andrew Whittemore at the University of North Carolina at Chappel Hill and published in Planning Perspectives. The article, “Zoning Los Angeles: A Brief History of Four Regimes,” is available for free online. If you love Los Angeles history, and you want to know more, I encourage you to download a copy.

Our official zoning history begins with the adoption of City Ordinance 42666 on 19 October 1921. Prior to this time, zoning was very simple, and had minor effect over land use. A 1904 ordinance, the first land use restriction in the US, prohibited land use for industrial purpose within residential districts. Five years later, in 1909, the first zoning ordinance was adopted. The ordinance simply divided the city into residential and industrial districts. Eleven years later, the City Planning Commission is created to develop a detailed zoning plan, the start of the 1st regime.

1st Zoning Regime

In the 1st zoning regime, interests favor the speculative real estate market. The regime begins with the advent of zoning in 1920 and runs to the mid-1930s due to the collapse of the stock market in 1929 followed by the Great Depression.

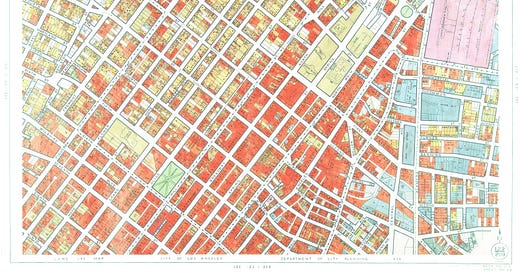

The newly created Los Angeles City Planning Commission soon produces a zoning plan that consists of five planning zones designated by the letter “A” through “E.” Each letter designates the type of activity allowed within each zone. Zone A is designated for single family homes, Zone B is designated for non-residential use, and Zones C, D, and E are designated for various levels of industrial use.

In line with the common thoughts of the time, city planners saw the urban core as the place for civic buildings and public space with residential areas forming small, contained, communities that surround the core. Single-family homes should be located along quiet interior streets while apartments and multi-family housing line major arteries. These arteries connect and denote the boundary of each community with commercial use limited to the area near major intersections.

We can clearly see this pattern today in old photos of the city and in parts of town today that have not yet been impacted by “in fill” development. As for public reaction at the time, they were none too pleased with the imposed constraints. Prior to zoning, a landowner could build whatever they wanted. The new zoning-code restricted land use and restrictions impacted land value. Los Angeles was undergoing a building boom and restrictive zoning was not beneficial for speculators who owned the wrong type of land.

The Commission soon learned that it was best to engage the public in their decision making. Public appeals to the City Council called for less restrictive land-use designations. Speculating small-scale owners of single-family land did not want to be restricted. Complaining to City Council, these owners were often granted an exemption or variance. This practice of “over-zoning,” or what we today call “spot” zoning, is a hallmark of the regime.

In addition to “over zoning,” the plan to limit commercial use to major intersections was doomed to fail because of the automobile. In 1924, the Los Angeles Traffic Commission issued their “Major Traffic Street Plan for Los Angeles.” The plan called for thirty-six 75-foot-wide thoroughfares to connect the districts and forty-eight radial routes. A later traffic plan tried to connect and widen some routes, creating a great circular highway around the city, but the scheme proved to be impractical. The domination of the automobile in dictating urban design had begun.

Very soon, property owners along the routes and thoroughfares insisted that their property be rezoned for commercial use. They argued that the noise and dirt from the road were too much for residential use and the high volume of traffic made the adjacent land highly accessible. Property values jumped by as much as 300 percent with the upzoning from residential use to commercial frontage. The ratio of land zoned for commercial use versus residential use jumped to 25 percent while the average for other cities was 9 percent. The design by city planners to have residential areas served by commercial space limited to major intersections was dead.

However, a few pockets of homeowner resistance against commercial over-zoning did emerge. The Los Feliz Improvement Association and the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce worked together to persuade the mayor to veto a plan to rezone Los Feliz Blvd. They claimed city planning would be a farce if every owner of a vacant lot could gain a higher price by obtaining a variance (which, if denied by city planning, could often be obtained from City Council by making a well-placed contribution). Plunging property values due to the market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Depression put an end to the speculative market and the 1st zoning regime.

2nd Zoning Regime

The major interests during the 2nd zoning regime favor low-density development of residential property. The regime begins in 1934 with the founding of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). In the years following World War II, the FHA will cater to large-scale single-family community developers and new home buyers. The 2nd zoning regime ends around 1960.

The initial years of the FHA focused on setting community standards. These standards benefitted some residents by removing commercial development. From 1936 to 1938, fourteen miles of street frontage was rezoned from multi-family to single family use and six miles of business frontage was rezoned for residential use. While the total amount of rezoned street frontage was small, federal policy helped to halt the practice of over zoning.

On the negative side, FHA lending practice resulted in the creation of red-lined areas throughout the city. An owner of land within a red-lined area could not obtain low-cost FHA funding to improve or maintain their land. This lack of funding resulted in extensive urban decay and worsened racial segregation since financially mobile people (most often white) could afford to move out of the area.

The concept of redlining was tied to the FHA practice of lending federally insured amortized mortgages based on a neighborhood rating scale of “best” to “hazardous.” A rating of “best” was assigned to socially and physically homogenous single-family districts. Whereas, people living within a “bad” or “hazardous” area, with its mix of racially diverse multi-family residents and commercial use, represented an unacceptable credit risk. Lending was not based on a given persons’ ability to repay, but on where they lived.

For large-scale developers and their buyers, the availability of FHA and post war GI bill loans was a major boon. Prequalified applicants, mostly white and middle class, buying a new home in a socially and physically homogeneous single-family district fit the FHA requirements exactly. Developers profited by providing the type of housing that FHA policy deemed best. And since the large-scale development of single-family homes required large tracts of open land, the result was explosive urban sprawl into the San Fernando Valley and beyond.

Originally, zoning plans for the San Fernando Valley called for the containment of housing within concentrated centers to allow for the preservation of profitable agricultural use. This concept lasted until the early 50s’ as a growing number of wealthy newcomers desired a turnover to urban use. The Valley’s 1955 Master Plan advocated that at least 50 percent of the land zoned for agriculture be rezoned residential. Rather than adhere to the original plan, city planning backed down. As zoning critic Richard Babcock later put it, it was a case of zoning “wagging the planning dog.” Most of the agricultural land was gone by the mid 1960’s and the planned urban centers had bled into a single mass.

The winners in this period were big developers and new homeowners. In the early postwar years, Los Angeles was called a “growth machine”, in which a developer elite, bolstered by government policy, stimulated growth. The profits of that growth returned to the elite, but also to a growing number of homeowners. Now, near its end, the rate of growth slowed. Land cost rose as single-family construction met the natural boundary of the mountains and ocean. The ongoing sprawl would push on elsewhere, but for the City of Los Angeles it was slowly coming to an end.

This concludes part I of a three-part article looking into the history of zoning in Los Angeles. I hope you found it interesting and look forward to Part II.